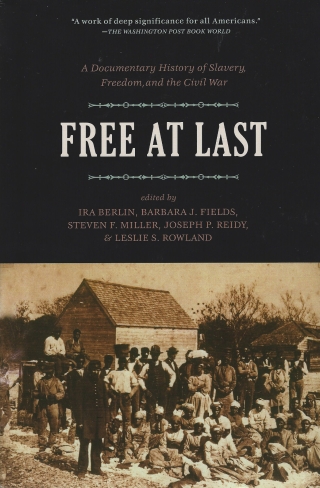

Free at Last: A Documentary History of Slavery, Freedom, and the Civil War

Free at Last makes available in a single volume the most moving and informative documents from the first four volumes of Freedom: A Documentary History of Emancipation.

The triumph and travail of emancipation emerge in the words of the participants – liberated slaves and defeated slaveholders, soldiers and civilians, common folk and aristocrats, Northerners and Southerners. The documents reveal the active role of slaves and former slaves in escaping slavery, aiding the Union cause as laborers and soldiers, transforming the war for the Union into a war against slavery, and giving meaning to their newly won freedom in a nation wracked by warfare and political upheaval.

Available in paperback and suitable for classroom use, Free at Last includes a convenient chronology of wartime emancipation and suggestions for further reading.

571 pp. Table of contents (pdf)

Free at Last received the Lincoln Prize, which is awarded annually to the finest scholarly work on the Civil War era.

Copies of Free at Last may be purchased from The New Press online, by telephone (800-233-4830), or by fax (212-629-8617).

Selected Documents from the Volume

- Missouri Unionist to the Commander of the Department of the West, May 14, 1861, and the Commander's Reply, May 14, 1861

Writing to the Union commander at St. Louis, a white Missourian sought and received assurances that the federal government would protect slavery. - Commander of the Department of Virginia to the General-in-Chief of the Army, May 27, 1861

General Benjamin F. Butler, the federal commander at Fortress Monroe, Virginia, explained his rationale for accepting and providing for fugitive slaves who had come into his lines, despite the Union's commitment to noninterference with slavery. -

Order by the Commander of the Corps of Observation, Army of the Potomac, September 23, 1861

In response to complaints that soldiers in his command were encouraging insubordination among slaves in the Union state of Maryland, General Charles P. Stone reminded his troops of their duty to uphold the laws, including those protecting slavery. - Order by the Commander of the Department of Virginia, November 1, 1861

General John E. Wool, the Union commander at Fortress Monroe, Virginia, instituted an arrangement in which ex-slave men employed by the army drew rations and were credited with wages – most of which were not paid to the workers but applied to the support of ex-slave women, children, and aged or disabled men. - Commander at Camp Nevin, Kentucky, to the Commander of the Department of the Cumberland, November 5, 1861; and the Latter's Reply, November 8, 1861

A general in the Union state of Kentucky found fugitive slaves useful as military laborers, but hesitated to employ them for fear of alienating their owners. His superior, General William T. Sherman, directed him to avoid the dilemma by excluding runaways from his lines altogether. - Governor of Maryland to the Secretary of War, November 18, 1861

When a Maryland slaveowner trying to recover his fugitive slave was driven away from a camp of Massachusetts soldiers, he appealed to Thomas H. Hicks, the governor of Maryland, who urged the Secretary of War to enforce the law, protect slave property, and thereby ensure the state's loyalty. -

Order by the Commander of the Department of the Missouri, November 20, 1861

The chief Union commander in the west, General Henry W. Halleck, cited military, rather than legal or political, grounds to justify excluding fugitive slaves from the lines of his army. -

Black Ohioan to the Secretary of War, November 27, 1861

Initially barred from serving as Union soldiers, black men in parts of the North nevertheless formed militia companies and began drilling on their own. A freeman in Ohio beseeched Secretary of War Simon Cameron for a chance to strike a blow against the rebels. -

Michigan Quaker to the Secretary of War, December 5, 1861

Writing to Secretary of War Simon Cameron, a white Northerner denounced the Union's policy of turning away fugitive slaves as militarily counterproductive and morally bankrupt. - Governor of Massachusetts to the Secretary of War, December 7, 1861, Enclosing an Excerpt from a Letter from an Unidentified Correspondent, November 28, 1861

Governor John A. Andrew protested when he learned that soldiers from his state had been ordered to engage in the “dirty and despotic work” of returning slaves to captivity. - Commander of the South Carolina Expeditionary Corps to the Adjutant General of the Army, December 15, 1861

Left behind on plantations by owners fleeing federal invasion, former slaves on the South Carolina sea islands generally remained in place and worked for themselves – to the annoyance of a commander of the invading force who had hoped to employ them as military laborers. - Maryland Fugitive Slave to His Wife, January 12, 1862

For John Boston, the triumph of his own escape to freedom within Union lines was tainted by the resulting separation from his wife.

First page of manuscript (image, 437K) - Northern Minister to a U.S. Senator from Massachusetts, January 29, 1862

Writing to a U.S. senator from his home state of Massachusetts, an antislavery clergyman in Union-occupied Virginia denounced the army's exaction of forced, uncompensated labor from fugitive slaves and questioned federal policies that upheld slavery. - Maryland Legislators to the Secretary of War, March 10, 1862, Enclosing Affidavit of a Maryland Slaveholder, March 1, 1862

Learning of incidents in which Union soldiers had thwarted attempts by slaveholders to recover escaped slaves, members of Maryland's General Assembly protested to Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton. -

Commander of the Department of North Carolina to the Secretary of War, March 21, 1862

When Union forces under General Ambrose E. Burnside captured New Bern, North Carolina, they received a warm welcome from the city's slaves, who were soon joined by hundreds of others from the surrounding countryside. Unsure how to proceed, Burnside turned to Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton for advice. - Resolution by the Washington, D.C., City Council, April [1?], 1862

As the U.S. Congress considered a proposal to emancipate slaves in the District of Columbia, Washington's City Council objected that doing so would lead to the influx of an unwelcome population. - Headquarters of the Defenses North of the Potomac to the

Commander of a New York Regiment, April 6, 1862

Citing a new article of war recently enacted by Congress and the valuable information slaves could provide, General Abner Doubleday instructed a regimental commander to admit fugitives into Union lines and treat them “as persons and not as chattels.” -

Virginia Slaveholder to the Confederate Secretary of War, May 2, 1862

Much to the disgust of slaveholders, runaway slaves sometimes found refuge within the ranks of the Confederate army, some of whose soldiers valued the owners' property rights less than the comforts servants could provide. Lamenting the subversive effects of such practices, a Virginia slaveholder urged the Confederate secretary of war to prohibit soldiers from employing slaves without their owners' consent. - Commander of the 3rd Division of the Army of the Ohio to the Secretary of War, May 4, 1862; and the Latter's Reply, May 5, 1862

When a Union general operating in northern Alabama informed Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton that he had promised protection to slaves who provided vital military information, Stanton approved, arguing that refusal to employ the services of slaves would handicap the Union war effort. - Proclamation by the President, May 19, 1862

After General David Hunter issued an order declaring free all the slaves in South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida, President Lincoln quickly overruled him and used the occasion to press his own plan for gradual emancipation, with compensation to owners. -

Commander of the U.S.S. Dale to the Commander of the South Atlantic Squadron, June 13, 1862

Former slaves on Hutchinson's Island, South Carolina, whose owners had fled advancing federal forces in late 1861, remained in place and cultivated the land for themselves. Their new lives were upended, however, when a Confederate counterattack the following June killed dozens, carried others back into bondage, and destroyed the crops they had hoped would guarantee their livelihood. -

Georgia Slaveholders to the Commander of the 3rd Division of the Confederate District of Georgia, August 1, 1862

Planters in Liberty County, Georgia, demanded stern action in response to widespread slave flight along the south Atlantic seaboard. Runaway slaves, they argued, were traitors who should be summarily executed under military law rather than prosecuted before slow-moving civil courts. - Governor of Iowa to the General-in-Chief of the Army, August 5, 1862

Advocating employment of black men by the Union army on entirely pragmatic grounds, Governor Samuel J. Kirkwood argued that a black man could drive an army team or stop a bullet as well as a white man. - Commander of the 5th Division of the Army of the Tennessee to a Tennessee Slaveholder, August 24, 1862

Writing to a former West Point classmate, General William T. Sherman explained why he would not return fugitive slaves to their owners. - Committee of Chaplains and Surgeons to the Commander of the Department of the Missouri, December 29, 1862

Although by late 1862 the federal government had pledged to protect fugitive slaves and encouraged the employment of those capable of military labor, the promise of protection was often hollow, as three officers at Helena, Arkansas, reported. - Northern Plantation Manager to the Commander of the Department of the Gulf, January 5, 1863

The manager of a sugar plantation in southern Louisiana cultivated by ex-slave wage workers complained that black soldiers and three of their officers – who were themselves free men of color – were disrupting labor and threatening his life. - Headquarters of a Confederate Cavalry Battalion to the Headquarters of the Confederate Department of Mississippi and East Louisiana, January 8, 1863

After capturing a former slave who had reached Union lines and then attempted to return home and liberate others, a Confederate officer asked his superiors how to deal with such “missionaries” of freedom. - Military Governor of North Carolina to the Commander of the

Department of North Carolina, January 20, 1863

Outraged by an incident in which ex-slave military laborers – accompanied by stewards from a Union navy vessel and servants of federal army officers – forcibly liberated one of the laborers' families, slaveholders complained to Edward Stanly, whom President Lincoln had appointed military governor of North Carolina. Stanly conveyed their protest to the state's military commander. - Commander of the Guard at Kenner, Louisiana, to the Headquarters of a Brigade in the Department of the Gulf, January 27, 1863

Former slaves employed by the army repairing levees near New Orleans, a Northern officer reported, were working and living in conditions that compared unfavorably to slavery. - General-in-Chief of the Army to the Commander of the Department of the Tennessee, March 31, 1863

General Henry W. Halleck privately advised General Ulysses S. Grant about the changing purposes of the war and the military benefits of emancipation. - Louisiana Freedmen to the Provost Marshal General of the Department of the Gulf, April 5, 1863, and Statement of the Commander of Camp Hoyt, Louisiana, April 5, 1863

Former slaves living on a plantation in southern Louisiana that had been abandoned by its owner received a Union provost marshal's permission to farm it on their own, only to have another claimant challenge their right to do so. At the freedpeople's request, a federal officer reported on what they had accomplished. - Black Former Officers in a Louisiana Black Regiment to the Commander of the Department of the Gulf, April 7, 1863

By late 1862, Union troops in southern Louisiana included “Native Guard” regiments, composed of free black men under officers who were also men of color. General Benjamin F. Butler had permitted the black officers to continue to serve, but his successor, General Nathaniel P. Banks, forced all but a handful to resign. A group of ousted officers urged Banks to reconsider his position. - Commander of the Department of the South to the Confederate President, April 23, 1863

After Confederate President Jefferson Davis ordered that captured black Union soldiers not be treated as prisoners of war, but instead be turned over to Confederate state authorities for punishment ranging from reenslavement to execution, Union General David Hunter warned Davis that mistreatment of black soldiers or their officers would be met with swift retaliation. - General Superintendent of Contrabands in the Department of the Tennessee to the Headquarters of the Department, April 29, 1863

Responding to a questionnaire circulated in early 1863, military superintendents of “contraband camps” in the Mississippi Valley (at Corinth, Mississippi; Lake Providence, Louisiana; Cairo, Illinois; and Memphis, Lagrange, Bolivar, Grand Junction, and Jackson, in western Tennessee) described the gritty reality of life in the settlements and evaluated the former slaves' prospects in freedom. - Testimony by the Superintendent of

Contrabands at Fortress Monroe, Virginia, before the American

Freedmen's Inquiry Commission, May 9, 1863

Captain Charles B. Wilder explained how fugitive slaves, once having escaped to Union lines, worked to liberate fellow slaves and spread the word of freedom deep in Confederate territory. - Former Superintendent of the Poor in the Department of North

Carolina to the Chairman of the American Freedmen's Inquiry Commission, May 25, 1863

Vincent Colyer, a Northern missionary who had supervised former slaves in Union-occupied North Carolina in 1862, described how they had assisted federal forces and supported themselves. - Officer in a Louisiana Black Regiment to the Commander of a Black Brigade, May 29, 1863

Writing to the chief recruiter of black troops in southern Louisiana, a Union officer praised the bravery of black soldiers in the battle of Port Hudson, many of whom had until recently been slaves. - Commander of the District of Northeastern Louisiana to the Headquarters of the Department of the Tennessee, June 12, 1863

A Union general described to his superiors the bloody battle of Milliken's Bend, Louisiana, the first test of combat for a brigade of newly enlisted black soldiers. - Northern Minister to the Secretary of War, July 11, 1863

When federal authorities in Washington, D.C., could not obtain enough military laborers locally, they ordered the forcible impressment of black men in coastal Virginia and North Carolina, wrenching hundreds from their homes and families. -

Mississippi Slaveholder to the Confederate President, July 20, 1863

After the fall of Vicksburg gave the Union control over the entire Mississippi River, slaveowners transferred thousands of slaves to areas more securely in Confederate hands rather than lose them to the Yankees. Fearing that the large-scale removals would undermine slave discipline and burden the resources of receiving regions, a slaveholder in eastern Mississippi advised President Jefferson Davis that desperate times called for desperate measures – including the conscription of enslaved men for Confederate military service. - Mother of a Northern Black Soldier to the President, July 31, 1863

Shortly after the battle of Fort Wagner, Hannah Johnson, the mother of a soldier in the 54th Massachusetts Infantry, urged President Lincoln to guarantee the proper treatment of captured black soldiers. In measured but heartfelt words she defined the president's responsibilities to the soldiers and their families and demanded that he fulfill them.

First page of manuscript (image, 473K) - Assistant Quartermaster at the Washington Depot to the Chief Quartermaster of the Depot, July 31, 1866

In Washington, D.C., where military laborers were in chronically short supply, an officer proposed that many of the menial tasks performed by black men in the city's military hospitals be assigned to convalescing patients, thereby freeing the black men for service at the quartermaster's depot. His enumeration of the black workers' duties, however, unintentionally revealed how vital they were to the hospitals' operations. -

Commander of the Confederate Trans-Mississippi Department to the Commander of the Confederate Army of the West, September 4, 1863

As federal forces threatened larger expanses of the South, Confederate commanders ordered the evacuation of slaves from endangered areas to prevent them from falling into Union hands. In a letter sent to each of his highest-ranking subordinates, General E. Kirby Smith, commander of Confederate forces west of the Mississippi River, emphasized that it was a question of removing slaves now or fighting them later. - Commander of a North Carolina Black Regiment to the Commander of a Black Brigade, September 13, 1863

Colonel James C. Beecher, commander of a regiment of former slaves from North Carolina, protested when his men were treated more like uniformed laborers than soldiers. - Massachusetts Black Corporal to the President, September 28, 1863

On behalf of the men of the 54th Massachusetts Infantry, Corporal James Henry Gooding protested the injustice of the Union's paying its black soldiers – in this case, Northern free men – less than their white comrades. - Inspecting Officer in the District of Northeastern Louisiana to the Headquarters of the District, October 10, 1863

Beginning in 1863, federal officials leased out abandoned cotton plantations along the Mississippi River near Vicksburg, mainly to Northern investors but also to a handful of freedmen judged competent to manage an estate. The lessees agreed to hire former slaves for wages and furnish subsistence to them and their families. But as an inspecting officer reported, raids by Confederate guerrillas, the lessees' cupidity, and other unfavorable circumstances beset the impoverished residents of most of the plantations. - North Carolina Freedmen to the Commander of the Department of Virginia and North Carolina, November 20, 1863

Black men who had been impressed to perform military labor for the Union army addressed an indignant petition to General Benjamin F. Butler.

Image of manuscript (468K) - North Carolina Slaveholder to the Confederate President, November 25, 1863

In an area not far from Union lines, a patrol guard and a pack of hounds helped prevent slaves from running away – at least until members of the patrol were drafted into the Confederate army. A slaveholder asked President Jefferson Davis to return the patrol to its former duties. - Marriage Certificate of a Black Soldier and His Wife, December 3, 1863 (image, 471K)

The marriage of two former slaves, Private Rufus Wright and Elisabeth Turner, was presided over by a black army chaplain, the Reverend Henry M. Turner. - Testimony by a Northern Abolitionist before the American Freedmen's Inquiry Commission, December 24, 1863

Francis W. Bird recounted his tour of the so-called government farms in southeastern Virginia, where former slaves lived and worked on estates seized from Confederate owners and supervised by the federal government. - Missouri Slave Woman to Her Soldier Husband, December 30, 1863

Martha Glover of Missouri, who remained enslaved after her husband enlisted in the Union army, described to him the burdens she and their children had borne since his departure. - Missouri Slave Woman to Her Soldier Husband, January 19, 1864

The wife of a slave who had enlisted in the Union army warned her husband against sending money in the care of her owner, in whose custody she remained, for fear he would intercept it. - Memorandum by a Tennessee White Unionist, January 27? 1864

As slavery in Union-controlled Tennessee eroded despite the state's exclusion from the Emancipation Proclamation, many slaveholders chose to negotiate new terms of labor with their nominal slaves rather than risk losing them altogether - Testimony by a Northern Woman, January? 1864

The wife of a Northern army chaplain recalled the fate of a settlement of black families that located with an officer's permission near Fort Albany, in northern Virginia close to Washington, D.C., until an order from higher military authority ousted them. - Officer in a Missouri Black Regiment to the Superintendent of the Organization of Missouri Black Troops, February 1, 1864

Lieutenant William P. Deming relayed to General William A. Pile his men's complaints that slaveowners were punishing their wives and children by assigning them heavy work normally done by the men. - Staff Assistant of the Superintendent of Freedmen for the State of Arkansas to the Superintendent, February 5, 1864

A Union officer reported on his visit to a woodyard established by private contractors on the banks of the Mississippi River and a nearby shantytown that was home to 183 former slaves, 96 of whom were “infirm & under age.” -

Affidavit of a District of Columbia Freedman, February 6, 1864

In April 1862, Grandison Briscoe escaped from Maryland to Washington, D.C., together with his pregnant wife, an infant child, and his mother. Within days, however, a slave catcher returned his loved ones to bondage. Nearly two years later, Briscoe described their fate. - Testimony by a Corporal in a Louisiana Black Regiment before the American

Freedmen's Inquiry Commission, February? 1864

After escaping slavery in 1861, Octave Johnson of Louisiana lived in the swamps for more than a year before entering Union lines near New Orleans. - Plantation Regulations by a U.S. Treasury Agent, February 1864 (image, 474K)

A broadside announced the rules governing the employment of black laborers on plantations in Union-occupied Louisiana. - Black New Yorker to the Secretary of War, April 18, 1864

Theodore Hodgkins of New York warned that failure to retaliate for the massacre at Fort Pillow, Tennessee – in which Confederate troops killed scores of Union soldiers, most of them black, after they had surrendered – would alienate black Americans from the Union cause. - Black Soldier in Virginia to His Wife, April 22 and May 25, 1864

In letters to his wife, Private Rufus Wright not only described a battle in which his regiment participated but also passed along more mundane news. - Black Sergeant to the Secretary of War, April 27, 1864

William J. Brown, a freeborn sergeant in a regiment composed mostly of former slaves, conveyed to the secretary of war his comrades' resentment that they were paid not only less than white soldiers, but also less than black civilian military laborers. -

Commander of a Black Brigade to the Headquarters of the Department of Virginia and North Carolina and the 18th Army Corps, May 12, 1864

Only on rare occasions could former slaves turn the tables on their masters by administering the punishments they had long received. General Edward A. Wild, commander of a brigade of black soldiers, reported one such occasion to a superior officer who had accused him of violating the rules of civilized warfare. - Black Acting Chaplain to the Secretary of State, May 18, 1864

Unwilling to appoint black men to military positions that entailed authority over white men, until early 1865 the U.S. War Department refused to commission black men as line officers, no matter what their qualifications. Applications for commissions as chaplains and surgeons – positions that did not involve battlefield command – were received with somewhat more favor. - Adjutant General of the Army to the Chairman of the U.S. Senate Committee on Military Affairs, May 30, 1864

Adjutant General Lorenzo Thomas, who was in charge of recruiting black soldiers in the Mississippi Valley, praised the men's military performance and, in so doing, added his voice to those advocating equal pay for black soldiers and their white counterparts. - Provost Marshal of Freedmen in the Department of the Tennessee to the Adjutant General of the Army, June 15, 1864

Colonel Samuel Thomas reported on the condition and prospects of the former slaves cultivating leased plantations along the Mississippi River between Vicksburg and Natchez, Mississippi. Although most of the freedpeople in that war-torn district were wage workers for Northern lessees, some were renters farming independently. - Soldiers of a Massachusetts Black Regiment to the President, July 16, 1864

Since July 1863, black soldiers in the 54th and 55th Massachusetts Infantry had refused to accept unequal compensation with white soldiers – a stand that came at considerable cost, including the impoverishment of many of their families. A year after opening their protest, convinced that the government had still not acted to correct the injustice, members of the 55th Massachusetts petitioned President Lincoln for immediate discharge and settlement of accounts. -

Maryland Former Slave to the Secretary of War, July 26, 1864

Writing from Boston, John Q. A. Dennis, who had become free only eight months earlier, asked Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton to authorize him to take his children from the slaveowners who still held them in bondage. - Maryland Black Soldier to the Mother of a Dead Comrade, August 19, 1864

A black soldier from Maryland consoled the mother of a friend who had died in combat. - Maryland Slave to the President, August 25, 1864

Maryland's exclusion from the Emancipation Proclamation left Annie Davis still enslaved. Insistent on her right to freedom, she demanded that President Abraham Lincoln clarify her status.

Image of manuscript (328K) - Acting General Superintendent of Contrabands in the South Carolina Sea Islands to the Provost Marshal General of the Department of the South, August 25, 1864

Displeased by former slaves' traveling about, fishing, or doing odd jobs instead of working steadily for a single employer, a newly appointed superintendent of contrabands proposed remedies informed by Northern practices regarding poor relief and vagrancy. - New York Black Soldier to the President, [August] 1864

Writing anonymously, a Northern black soldier stationed in Louisiana described the toll that hard labor and short rations were taking on the men of his regiment. - Commander of a Black Brigade to the Commander of the District of

Eastern Virginia, September 1, 1864

When a group of ex-slave men working as Union military laborers returned home to liberate families and friends, they were accompanied by a detachment of black soldiers. The soldiers' brigade commander reported the outcome of the dangerous expedition. - Missouri Black Soldier to His Enslaved Daughters, and to the Owner of One of His Daughters, September 3, 1864

Private Spotswood Rice promised his daughters – and warned the woman who owned one of them – that their liberation was at hand.

- Superintendent of the Organization of Kentucky Black Troops to the Adjutant General of the Army, October 20, 1864

General James S. Brisbin described to his superiors how the “jeers and taunts” that white Union soldiers had directed toward newly enlisted black soldiers were silenced by the latter's bravery under fire. - Maryland Lighthouse Keeper to a Baltimore Judge, November 6, 1864

Shortly after a new state constitution abolished slavery in Maryland, a unionist observer described the efforts of local citizens to nullify the former slaves' freedom. - Maryland Black Minister to the Superintendent of the Middle Department Freedman's Bureau, November 11, 1864

A black minister in Baltimore, Maryland, informed a military official that a secessionist family was forcibly retaining black people in bondage, defying the state's recent abolition of slavery. - Statement of a Maryland Freedwoman, November 14, 1864

Freed by the adoption of a new state constitution that abolished slavery, Jane Kamper contested her former owner's attempt to keep her children under his control by having them apprenticed to him. - Mother of a Pennsylvania Black Soldier to the President, November 21, 1864

Apprehensive about her son's safety and her own welfare, the elderly mother of a black soldier petitioned President Lincoln for his release from further service, on the grounds that he was her sole support. - Affidavit of a Kentucky Black Soldier, November 26, 1864

Threatened by their owner, the wife and children of Joseph Miller had accompanied him when he enlisted in the Union army. Miller described the ordeal that followed the expulsion of his family from the camp in which they took refuge. - Kentucky Black Soldier to the President, December 4, 1864

A black soldier unsuccessfully sought a discharge so that he could provide for his wife and children, whose owner refused to maintain them. - Escaped Union Prisoners of War to the Provost Marshal General of

the Department of the South, December 7, 1864

Two captured Union officers who slipped their guards in Charleston, South Carolina, recounted the saga of their safe return to federal lines with the help of the city's free and enslaved black people and German immigrants. - Affidavit of a Kentucky Black Soldier, December 15, 1864

A black soldier at Camp Nelson, Kentucky, protested the expulsion of his wife and ailing daughter from the camp, where they had taken refuge after being threatened by their owner. -

Commander of the 3rd Separate Brigade, 8th Army Corps, to the Headquarters of the Middle Department and 8th Army Corps, December 15, 1864, Enclosing a Circular by the Brigade Commander, December 6, 1864

General Henry H. Lockwood reported how the apprenticeship system in Maryland worked, and to whose benefit. - Black Residents of Nashville, Tennessee, to the Union Convention of Tennessee, January 9, 1865

In a petition to a convention of white unionists that was considering reorganization of the state government and the abolition of slavery, black Tennesseans argued that black men were fit to exercise all the privileges of citizenship. - Provost Marshal of the 2nd Subdistrict of North Missouri to the

Provost Marshal General of the Department of the Missouri, January 12, 1865

Expecting a state constitutional convention to abolish slavery, some slaveholders in Missouri showed less interest in retaining their slaves than in shedding responsibility for them, a Union officer informed his superior. - Meeting between Black Religious Leaders and Union Military Authorities, January 12, 1865

A Northern newspaper reported the proceedings of a remarkable gathering in Savannah, Georgia, in which twenty black ministers and lay leaders met with Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton and General William T. Sherman to consider the future of the thousands of slaves freed by the march of Sherman's army. -

Kentucky Black Soldier to the Secretary of War, January 26, 1865, Enclosing Two Letters

Private Aaron Oats believed that his service to the Union entitled him to assistance in liberating his family. In a letter to the secretary of war, Oats enclosed two letters he had received, one from his wife and the other from her owner. - Chaplain of a Louisiana Black Regiment to the Regimental Adjutant, February 1, 1865

In a report to the Bureau of Colored Troops, the white chaplain of a Louisiana black regiment described the changes he had witnessed among his men since their enlistment. - Chaplain of an Arkansas Black Regiment to the Adjutant General of the Army, February 28, 1865

The chaplain of a black regiment in Arkansas noted the importance of marriage to the freedpeople, who regarded their wartime emancipation as a step toward “an honorable Citizenship.” - Affidavit of a Kentucky Black Soldier's Widow, March 25, 1865

After her husband enlisted in the Union army in late 1864, Patsy Leach endured abuse at the hands of their enraged owner, a Confederate sympathizer in Kentucky. Fearing for her life, she fled with her youngest child, leaving four other children behind. -

Affidavit of a Kentucky Black Soldier, March 29, 1865

When Congress adopted a joint resolution in March 1865 freeing the wife, children, and mother of every black soldier, slave men in Kentucky (where slavery remained legal) responded with a renewed surge of enlistments. Slaveowners threatened volunteers and their families with violence, and local police and slave patrols tried to obstruct slaves' flight to recruitment centers. A soldier recounted how he and his wife had been foiled in their first attempt to escape. -

Missouri White Farmer or Farm Laborer to a White Farmer, Spring? 1865

A farmer or farm laborer addressed a courteous protest to a neighbor who had introduced a black settler into the area, possibly as a renter or hired hand. -

Louisiana Black Soldier to the Secretary of War, May 1865

Seventeen-year-old Warren Hamelton, a soldier who had been imprisoned for desertion, appealed his conviction on the grounds that the government had failed to fulfill its obligations to him and he was therefore unable to support his mother. -

North Carolina Black Soldiers to the Freedmen's Bureau

Commissioner, May or June 1865

At the end of the war, black soldiers stationed near Petersburg, Virginia, wrote to the commissioner of the Freedmen's Bureau to protest the suffering of their wives, children, and parents at a settlement on Roanoke Island, North Carolina. - Delegation of Black Kentuckians to the President, late June, 1865

Fearing that President Andrew Johnson might lift martial law in Kentucky – a Union state where slavery was still in force – six black men traveled to Washington to inform him of “the terrible uncertainty of their future” under the state's oppressive laws. -

Michigan Black Sergeant to the Commander of the Department of South Carolina, August 7, 1865

A black sergeant stationed in South Carolina after the war complained to the state's military commander when a post commander failed to render justice to a freedman who had applied to him for assistance. - Tennessee Unionist to the Tennessee Freedmen's Bureau Assistant Commissioner, August 8, 1865

Left behind when their Confederate owner fled before a Union advance in 1863, slaves on a farm in Tennessee supported themselves independently until near the war's end, when the proprietor's return threatened their hard-won self-sufficiency. -

Affidavit of a Former Alabama Slave, August 14? 1865

Liberated by Union forces in northern Alabama in 1862, twelve-year-old Amy Moore, her younger sisters, and her mother were reenslaved in 1863 under a Kentucky law that prohibited freed slaves from entering the state on pain of arrest as runaways. Still in bondage months after the end of the Civil War, Moore recounted how she and the other members of her family had been jailed and sold at auction. -

Missouri Black Soldier to the Secretary of War, August 22, 1865

On behalf of comrades from Missouri and Tennessee, a black soldier wrote to the secretary of war concerning the men's concern about their families, their dissatisfaction with routine duties, and their disdain for a particularly obnoxious officer. -

Statement by a Tennessee Black Sergeant, September 11, 1865

For former Confederates, nothing more vividly demonstrated the humiliation of their defeat than the presence of black soldiers. Two white policemen in Memphis vented their anger against a black sergeant who refused to be cowed by threats. - Affidavit of a Tennessee Freedman, September 13, 1865

After the war, a former slave from Tennessee described the horrific consequences of his failed bid to reach Union lines in 1864. - Maryland White Unionist to the District of Columbia Freedmen's Bureau Assistant Commissioner, September 14, 1865, and Affidavit of a Maryland Freedwoman, September 18, 1865

When Derinda Smothers's fourteen-year-old son ran away from their former owner, to whom he had been apprenticed without her consent, the boy was recaptured and punished with a whipping, while Smothers was jailed for encouraging his escape. - Order by the Commander of a Kentucky Black Regiment, October 5, 1865

When former slaves in a Mississippi town sought to establish a school, they enlisted the aid of two noncommissioned officers in a black regiment stationed nearby. - Kentucky Black Sergeant to the Tennessee Freedmen's Bureau Assistant Commissioner, October 8, 1865

In a letter to an official of the Freedmen's Bureau, Sergeant John Sweeny of Kentucky emphasized the importance of education to his people.

First page of manuscript (image, 2.2 MB) -

Officer in a Kentucky Black Regiment to the Headquarters of the Regiment, November 15, 1865

Armed with an order from General John M. Palmer, the military commander in Kentucky, a black sergeant attempted to move his wife from the home of her former owner, only to be jailed by civil authorities. His company commander recounted the episode to the commander of the regiment, whose endorsement and that of General Palmer indicated that such persecution of black soldiers was common. - Tennessee Black Soldier to the Commander of the Military Division of the Tennessee, November 19, 1865, and Commander of a Tennessee Black Regiment to Division Headquarters, December 14, 1865

A black soldier stationed in Alabama protested that his regimental officers forbade the wives of the enlisted men to visit camp, prompting his regimental commander to defend the practice as a disciplinary measure and cast aspersions on the men's attachment to the women they regarded as their wives. - Mississippi Black Soldier to the Freedmen's Bureau Commissioner, December 16, 1865

Outraged by Mississippi's newly enacted black code and by outbreaks of violence against freedpeople, Private Calvin Holly wrote the Freedmen's Bureau commissioner to describe conditions and propose a solution. - South Carolina Black Soldier to the Commander of the Department of South Carolina, January 13, 1866

With Union victory won and emancipation secure, the spokesman for soldiers in a black regiment asked their departmental commander to allow them to leave the service and rejoin families who were suffering in their absence. - Statement of a Tennessee Freedwoman, February 27, 1866

Months after the war, one of four black women whose work in military hospitals had taken them to Georgia, Tennessee, and Alabama recounted their travels before a Freedmen's Bureau official to whom they had applied for assistance in recovering unpaid wages. -

Kentucky Black Soldiers to the President, July 3, 1866

More than a year after the war ended, soldiers serving along the Mexican border compared their service to the Union with the shoddy treatment they and their families had endured and challenged their commander-in-chief to make good the nation's promises to them. - Affidavit of the Wife of a Discharged Georgia Black Soldier, September 25, 1866

The wife of a discharged soldier paid a high price for his association with the Union army. - Testimony by an Alabama Freedman before the Southern Claims

Commission, July 31, 1872

With slavery in northern Alabama unravelling during 1862, Alfred Scruggs became free in fact if not at law. In postwar testimony, Scruggs described how he and his wife had worked to acquire livestock of their own, only to lose it to federal impressment parties in 1864. - Testimony by a South Carolina Freedman before the Southern Claims Commission, March 17, 1873

Alonzo Jackson, during the war a slave in Georgetown, on the South Carolina coast, described to a postwar federal commission the assistance he had rendered Northern escapees from the prisoner-of-war stockade at Florence, in the interior of the state. - Testimony by a Georgia Freedwoman before the Southern Claims Commission, March 22, 1873

The Union troops who in late 1864 liberated Nancy Johnson and her husband from slavery also stripped them of property they had painstakingly accumulated while in bondage. Years later, she recounted to a federal commission the rigors of life in the Confederacy and the tribulations of an impoverished freedom. - Testimony of an Arkansas Freedman before the Southern Claims Commission, June 6, 1873

Robert Houston of Arkansas recounted his wartime experiences as a slave on a plantation, a fugitive from Confederate labor impressment, a laborer on a federal gunboat, an independent woodcutter, and a Union soldier. -

Testimony by a Georgia Freedman before the Southern Claims Commission, July 17, 1873

Slaves who accompanied their owners into the Confederate army as personal servants often learned of federal emancipation policies before their families and friends. When they returned home, their knowledge spread quickly. Samuel Elliott, a former slave from Georgia who had been taken to the frontlines in Virginia, told a postwar federal commission of the result on his plantation.